Most of us would accept that the leading example of a swimmer capable of swimming multiple events is Michael Phelps. In the Beijing Olympic Games he entered and won eight events – the 100 butterfly, 200 butterfly, 200 IM, 400 IM, 4×100 free, 4×200 free and 4×100 medley.

The ABC News website recorded the event in these glowing terms Â

| Phelps already made history by matching Spitz’s seven golds — Now he’s one-upped Spitz’s record count, cementing his place as one of the best athletes of all time.Superman. Magical. The King. The Dolphin. The Fish. The Phenomenon.

These are just some of the words being used to describe the face of the XXIX Summer Olympics in Beijing, Michael Phelps |

Few of us would disagree. Eight events in a week: what an incredible feat of application, training and commitment. By the time he swam in Beijing Phelps had been swimming at an Olympic level for eight years. He was an internationally hardened competitor. He had to be, just to survive.

But as it turns out the Phelps’ Beijing schedule was an easy week compared to the race program followed by many junior swimmers around the world.

For example in two recent meets, Alley, the swimmer mentioned earlier in this book swam in ten races in two days and six races in one day. Â Â Â

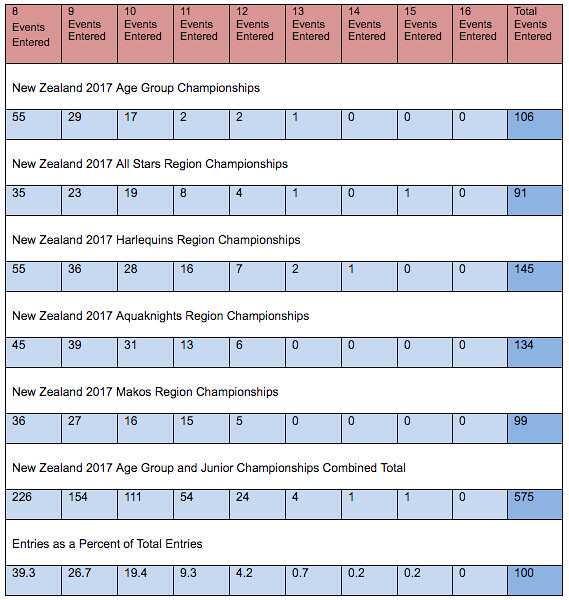

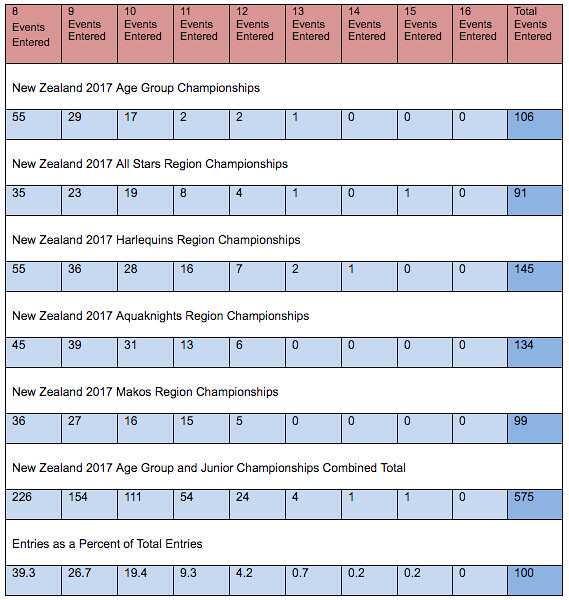

But in case you are thinking Alley might be an unrepresentative anomaly I looked at the 2017 New Zealand Age Group Championships and the 2017 New Zealand Junior Championships. I noted the number of races entered by every swimmer and made a record of the number of swimmers who entered and swam eight or more events. In other words swimmers who matched or exceeded Michael Phelps Beijing schedule. The results were stunning and are recorded in the table below.

The regions shown on the table represent different areas of New Zealand. All Stars are clubs from the lower North Island, Harlequins are clubs in the northern North Island area, Aquaknights are clubs from the centre of the North Island and Makos are clubs from the South Island. Each column in the table shows the number of swimmers entered in between eight and sixteen events.

So what does this table say?

It tells us that at the combined Age Group Championships and the four regional Junior Championships a total of 575 swimmers swam in programs the same as or harder than Phelps Beijing program. 349 swimmers (60.7%) had programs with more events than Phelps. 226 swimmers (39.3%) had the same number of events as Phelps Beijing schedule. Two swimmers came within one event (15 events) of doubling Phelps Beijing total. The Harlequins region had the highest number of big entries with 145 swimmers. Harlequins is also New Zealand’s strongest and culturally most diverse region; lending weight to the idea that the better the junior the more they will be exploited.

Doing the analysis I was surprised at the disproportionate number of names that appeared to be of Asian or Polynesian origin. Of course it is not appropriate to draw conclusions from a name. However of the 575 swimmers entered in eight or more events a far higher proportion than the general population appeared to have Asian and Polynesian names. If that is true I suspect it reflects the well-known Asian reputation for pushing very hard for results; sometimes too hard it appears and the early physical maturity of many Polynesian young people.

However the ethnic conclusions are tenuous and unproven. What is not tenuous or unproven is the stunning number of young people flogged through an impossible number of events and facing an early exit from the sport.

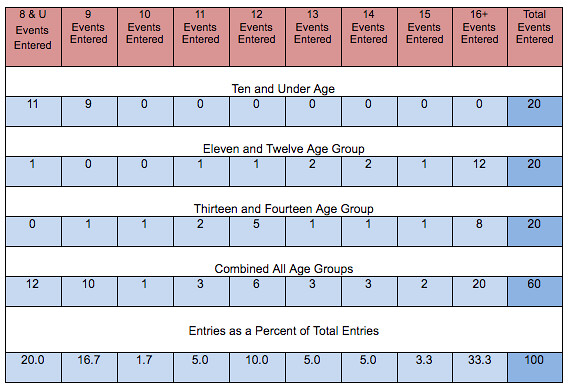

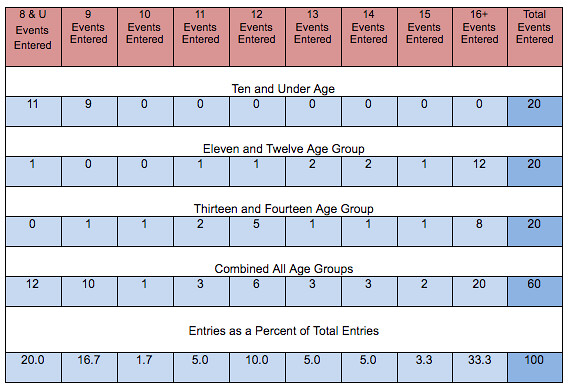

Over racing is not only a New Zealand problem. Swimmers everywhere are over raced. For example, a quick look at the results of the first six finals in the 2107 Florida Gold Coast Junior Olympics showed that the sixty swimmers involved swam the following number of events. Â

Here again the numbers are stunning. Thirty three percent of the swimmers competed in sixteen or more races in just three days. What Phelps took a week to do these guys do every day – or close to it. And still administrators, coaches and parents wonder, why do we have and 80% to 90% drop-out rate?

Entering this number of swims in an age group championship is bad. The fact it doesn’t work as a development tool for the sport is clearly demonstrated by the failure rate of junior championship winners to progress to Open National success. And yet here are the headlines that get printed by the national Federation in support of mass entries.

| The pair finished with seven gold medals each to top the individual medal count. Freesir-Wetzell gained two further wins today in the 10 & under division 200m medley and 100m freestyle. She was the leading medalist overall with nine medals, comprising seven gold and two silver.

Tawa’s Jack Plummer had the most medals with nine comprising four gold, four silver and a bronze with today’s sole win in the 11 years 100m breaststroke. |

Short sighted administrators actually see merit in the news that a teenager has been flogged through a dozen races in two days. And as for the clubs that participate; that too is a scandal. I wonder what their committees think of the 18th century custom of using 12 year olds in British coal mines. Oh, I understand the motivation; as parents flock to the clubs that exploit the most in the hope their child will be the next junior champion.

There may be some who find this opinion less than persuasive. Let’s see what the experts say. Several Olympic Games ago the American Aquatic Research Centre in Boulder, Colorado scanned the hand joints of every member of the American Olympic team. Their purpose was to determine what portion of the swimmers had been early developers, on time and late developers. Evidently the rate at which the hand joints close can measure an individual’s physical maturity. Of the forty athletes tested only two had matured early, five had matured on time and the majority were late developers.

The American scientists concluded that the probable explanation for the stunning failure of swimmers who develop early is the almost impossible burden of handling their early success, followed by the struggle to stay ahead of late developers who were such easy beats a few years earlier. Over and over again it happens; junior winners find it impossible to handle the “shame” of being beaten by slow swimmers who used to be miles behind; often didn’t even make finals. Interpreting it all as a failure on their part the early superstars go off to the local surf patrol or to a water polo team. And it’s absolutely understandable.

Take Ashley Rupapera for example. In 2006/7 she was amazing; at 14 years old she claimed her second national age group record with a 100IM time of 1:05.30. In the Junior Championships she entered 13 individual events, swam in 22 races and won four gold medals and two silver medals. I don’t know what Ashley is doing today. However, sadly, it does not include elite New Zealand swimming.  Â

Age group championship meets are the scene of too much hurt. At the beginning of the week keen, enthusiastic, happy young people arrive full of anticipation, coached and honed to a competitive edge. Parents dash around the pool checking that their charge’s start list seed times have been properly entered and locating the town’s best source of pasta. Coaches patrol the pre-meet practice with all the intensity of an Olympic warm up. International swim meet promoters would die to be able to create the nervous energy present at the beginning of your average age group championship.

By the end of the first morning’s heats you can detect the mood beginning to change. The problem is thirty swimmers enter an event, eight make a final, three get medals and one wins. Potentially there are twenty nine disappointed swimmers and fifty eight disappointed parents who can’t wait to get back to the motel for their treble gin and tonic to ease the pain. It’s a disappointment born out of expectations set far too high.

As each day goes by the mood darkens and deepens. An adult’s most valuable skill is providing comfort to another sobbing teenager. The transformation is stunning. The tremendous high of the first morning slumps during the day; is momentarily revived at the beginning of day two, only to slump even further. By day four all I want to do is get out of there and make sure no swimmer ever goes back. For someone whose heart is in seeing athletes soar, junior championships are no fun at all.

Several years ago there was a good article on the US Junior Nationals in the USA Swimming magazine “Splash”. In it USA Swimming seem to be aware that their event needed to avoid many of the problems characteristics. This is what they said:

| “Along the way, however, many coaches and others within USA Swimming saw a disturbing trend. Instead of a whistle stop on the way to senior national and international competition the Junior nationals were embedding themselves as a destination.” |

The Americans have done some good things to avoid damaging the nation’s youth. First of all their junior event is not a normal age group meet. Everyone up to a relatively old 18 can swim in the event. This avoids youngsters being over exposed at too young an age. Secondly, the qualifying standards are really tough. They reflect the “older” cut off age. An athlete has to be pretty quick just to make the cut. There’s a fair chance swimmers that fast will have the experience and maturity to handle the occasion. Thirdly, names included on the meet’s list of alumni suggest their “Juniors” are working as a transition between Sectional and International athlete. “Splash” tells me that Gary Hall, Aaron Peirsol, Ian Crocker and Michael Phelps all swam here. That’s a pretty impressive list. It appears that winning is not essential either. For example, Phelps never won the event, but he seems to have come through unscathed.

Competition hurts, which means that when a person gets hurt often enough they eventually go off to do something else. The rule of thumb is 100 races a year. Stick to that number. Your swimmer’s future probably depends on it.